Its massive trees are a setting akin to the Northwoods. Situated on a rolling ridge, on misty days one can almost hear the voices of the past whisper in a visitor’s ear. St. John’s Cemetery on Wolf Road is one of Mokena’s most hallowed places, it being the final resting place of a vast and impressive array of figures from our community’s history. As one leaves the busy thoroughfare, traffic becomes a distant hum, and as the guest wanders out into the sea of weather-beaten tablets and beholds the names thereon, it becomes clear that each and every one holds a story. An entire volume could be written about this place, and a thick one at that. It’s nearly impossible to highlight only a handful of the hundreds of people whose earthly remains lay here, and this piece will just barely skim the surface.

The history of the St. John’s congregation, one of our fair community’s oldest religious institutions, takes us back almost to the very birth of the village. A group of faithful German and Swiss families beginning worshipping together as early 1858 in Mokena’s schoolhouse, after a nasty falling out with their former brethren, the congregants of the Immanuel Lutheran church. Their preachers were itinerant ministers, and the flock finally gained their own resident man of the cloth when Prussian-born Reverend Wilhelm Meyer came onto the scene on New Year’s Day 1862. He brought the group into a new era, and on March 1st, the German United Evangelical St. John’s Church was founded, a mere ten years after Mokena was first platted. The devotees built themselves a simple yet refined church on the town’s Public Square the same year, and fitting themselves with all the trappings of a proper congregation, also began planning their cemetery at the same time.

The trustees of the church found willing property sellers in members John and Helena Schiek, who sold them a tract of land south of town for a burial ground on May 23rd, 1863 for $175, or about $4,000 in today’s figures. Situated on an old Potawatomi trail that is now Wolf Road, this slice of prairie was identical to the rest surrounding the small railroad hamlet that was Mokena in this time. The first burial took place that September, and over the years, the cemetery grew as the St. John’s congregation did. After 63 years of service, five additional acres were tacked on to the northern edge of the burying grounds in August 1926. Not a single monument profiled in this piece contains a word of English; each one is inscribed in the German tongue, with many bearing the regal gothic font chiseled in stone popular in the 19th century. While all of the founding members of St. John’s became proud Americans, they never forgot where they came from.

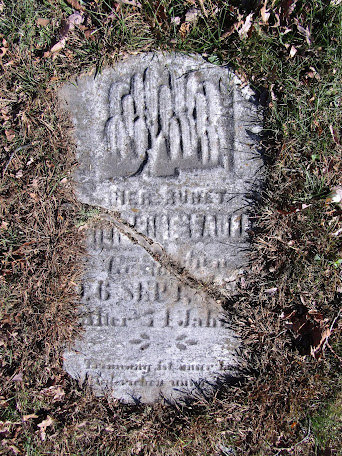

Tradition holds that Philippine Laufer was the first person to be interred in these historic grounds. Her bones lie in the middle of the cemetery, her gravestone long since toppled from its base and lying flush with the earth. The simple slab bears a smoothly worn motif of a weeping willow, a common symbol of mourning in the mid-19th century. This stone and this ancient grave represent chapter one, day one of this cemetery’s history.

Philippine Laufer was born to the world in 1789, and lived most of her life in Bavaria, in a world far removed from her future home. She likely made the arduous journey to America with her adult son George, who first set foot on our shores in the summer of 1846, escaping his homeland two years before it was torn asunder by revolution. After being processed through the port of New York, all paths led to Chicago, and from thence the Laufers settled in eastern Will County, then quickly becoming a haven for German-speaking folk. The newly-arrived family made their rustic pioneer’s homestead on the north side of what would become 183rd Street on the outer fringe of modern-day Frankfort Township, atop a high crest that would come to be called Summit Hill. The building materials for their first domicile were brought from Chicago by a span of oxen; only later would a more spacious home be built directly across the road.

The grave of Philippine Laufer, traditionally said to be the first in St. John's Cemetery. (Image courtesy of Michael Philip Lyons)

Philippine Laufer would come to have six grandchildren through her son, who in 1850 married Eva Utzinger. All of these children lived to adulthood, each one having families of their own, and while their surname gained an additional letter and came to be rendered as Lauffer, their descendants still live in and around Mokena to this day. Philippine drew her last breath on September 6th, 1863, and as the ground was broken in the new cemetery to receive her earthly remains, Abraham Lincoln sat in the White House, and the bloodbath at Chickamauga, Georgia, in which numerous Mokena men took part, was only a little more than a week away.

The Civil War and its dark days are intimately associated with this place, for not only were St. John’s church and cemetery born during this time of conflict, but at least eight of its Union heroes are interred here. One of them was a young man named George Treuer, who came from a small village called Hügelheim in the far southwestern German grand duchy of Baden, a mere stone’s throw from the French frontier. History doesn’t tell us when or why he made the trek to America, but Treuer lived in the environs of Mokena by 1860, when a federal census taker found him living as a farmhand on the property of Jacob Bauch, just north of today’s intersection of Wolf Road and 191st Street.

While working at the craft of shoemaking, the Civil War erupted in April 1861, and a month later, George Treuer came to the defense of his adopted homeland by rallying to the flag with the 20th Illinois Volunteer Infantry, mustering into the regiment on June 13th at Joliet. The unit saw hard service, and the February 1862 campaign in northern Tennessee to capture the rebel Fort Donelson on the Cumberland River was a typical example. The march to the battlefield spelled untold hardship for Private Treuer and his comrades. In the lead up to the fight, he and his brothers in arms camped in the open air during a punishing winter rain, and upon waking up the next morning after a fitful night, found their blankets frozen solid in a deep freeze. Due to these harsh conditions, an exhausting illness set in on the young man. During the battle for the fort, in which the Union men suffered over 2,600 casualties, a rebel ball passed through the fleshy part of George Treuer’s leg. His blood was not shed in vain, as the action was a major victory for the North.

Treuer served with the 20th Illinois until he was discharged from the unit upon the expiration of his term of enlistment in June 1864. Despite his wound, he volunteered yet again in the army, this time for duty with the Veteran Reserve Corps in February 1865. Sometimes called the Invalid Corps, they were a group of volunteer Union soldiers who were physically incapable of carrying out normal charges, and thus manned forts, guarded sites in the nation’s capitol, and tasks of this nature. Exactly a year after the war’s end, George Treuer married Anna Mavis in April 1866, and not long thereafter began a new chapter of his life, namely fathership, with the birth of their daughter Elizabetha in the fall of 1868. For a brief period in these years, its bookends unclear through the fog of time, Treuer also kept a saloon in Mokena, catering to the village’s thirsty German-Americans.

The time-honored headstone of Civil War hero George Treuer. (Image courtesy of Michael Philip Lyons)

The war never really ended for Treuer, who was burdened by the pain of a battle wound that never properly healed, and the after effects of the debilitating sickness from that wet, freezing night in Tennessee. At the end of 1871, not two months after Chicago was ravaged by the Great Fire, the young veteran’s health issues were compounded when his weakened lungs were attacked by tuberculosis. George Treuer lost this battle, and he passed away on December 7th, 1871 at the age of 30 years. He was buried in a simple grave at St. John’s Cemetery outside town two days later. In time his loved ones had a proud marker erected over his mortal remains. Nowadays a thick crop of day lilies surround it in the warm months, this gravestone holding silent watch over a warrior hero’s dust. When the sun hits its ancient, weathered letters in just the right way, they can be read as clearly if they were chiseled yesterday. In the rays’ relief, the figure of a slender hand can be seen picking up a broken chain, its severed links representing a centuries’ old belief that the soul was tethered to the body by a golden chain.

Treading slightly northwest from George Treuer’s grave and down the ridge, one comes upon another time-honored plot, this one marked by a traditional gravestone with a rounded top, bearing the icon of a hand pointing toward the heavens. Here the earthen mound of Dr. Johann Andreas Grether is beheld. One of the many early Mokenians with Swiss roots, Dr. Grether was born in the winter of 1807 near the city of Bern. Any details on the doctor’s early years are sparse, but it has been confirmed that he came to our country in 1852 with his wife Catharina and a daughter whose name has been long since lost to the ages. Three years later, Johann Andreas Grether was joined in America by his son Peter, who was finally able to make the journey.

It was in this decade that Dr. Grether made Mokena his home, not long after the Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific Railroad was built, and the village was first platted. Nevertheless, it was a period of hard times, as Catharina Grether died in 1854, whereupon a year later, Johann Andreas married the widow Elisabetha Schiffmann. As the United States entered the Civil War years, the family was deeply impacted by another tragedy when Peter Grether died as a Union soldier at Vicksburg, Mississippi in August 1863, being felled by disease. In this era, Dr. Grether humbly administered to our village’s sick and injured, and became successful enough in his practice that he was able to afford buying property in the new town. In the fall of 1867, he acquired a roomy house on today’s Front Street that is still with us a century and a half later, of late housing Le Angeline’s salon.

Johann Andreas Grether died September 5th, 1869 at the age of 62, having surpassed the life expectancy of his time by more than two decades. Decades later, Mokena old timers would look back on his funeral, and remember it for a very unique reason. While friends and family were watching over his bier in the late doctor’s home, the figure of a woman clad completely in black was seen to enter the room. The others became aware of her presence, and while many laid eyes on her, no one knew her. After staying just long enough to make herself known, she passed into another room, whereupon another mourner gently went after her to see if her identity could be ascertained. Upon reaching the other room, she was nowhere in sight, and had disappeared into thin air. In the minds of those there that day, the only possibility was that she was a ghost.

St. John’s Cemetery is home to many understated, spartan graves. However, numerous larger, statelier remembrances can also be seen within the grounds. They are the grand monuments to even grander lives. They are not so much displays of wealth, but of love felt. One such obelisk marks the family lot of Franz Maue, a man who exemplified the iron-willed fortitude of the pioneer. He first saw the light of day on February 15th, 1805, in the small, picturesque town of Katzweiler in today’s western Germany. He came of age in agricultural surroundings, and would be a farmer his whole life. Along the way, he also learned the trade of tailoring, as a way to buttress his income during spells of bad weather. He was wed to Elisabetha Berdel, a native of a neighboring village on May 27th, 1827. Together they would bring nine children to the world, of which six lived to adulthood.

The Maue family set sail for America in 1847, and undertook a crossing of the seas in 21 days, which to modern readers may sound unbearably rough, but in their day, it was considered an easy trip, as far as cross-Atlantic sailings went. During the journey, Franz and Elisabetha’s 16-year-old son Daniel met Sarah Mast, member of another America-bound family. Seven years later, the two would be married, as a result of what would come to be called their “voyage courtship.” Landing was made in New York, and the Maues then made their way up the Hudson River, and followed the Erie Canal to Buffalo. From there they entered the Great Lakes by boat, and eventually reached Chicago, then a fledgling rural outpost. As would later be remembered by a family member, Franz Maue then “drove into the country, looking for a good location.” He reached what we now know as Frankfort Township, the vanguard of the first wave of Germanic emigration to our community, and found in the soil here exactly what he was looking for in an American homestead. Maue immediately got to work setting up his family’s hearth here; by and by he acquired land, and eventually could look over an estate of 160 acres that was all his. His holdings, which were located northwest of where Mokena would come to stand, would ultimately be bisected by the Rock Island railroad. By 1862, a sizeable chunk of his farm had passed into the hands of his oldest son Daniel, while Franz himself still oversaw a large tract along our current 191st Street. At least two homes stood on this acreage, one east of the modern-day intersection with 104thAvenue, and another on the northwest corner of LaGrange Road’s crossing. Every trace of these have long since disappeared from our landscape.

The fine craftsmanship of the stone etching on Franz Maue's monument. (Image courtesy of Michael Philip Lyons)

The Maues were also founding members of the St. John’s congregation, and Franz would serve the flock as a member of the church’s council. Franz Maue passed away at his home outside town on March 2nd, 1879, after having been hit by a stroke. His respected status in our community is evidenced by a long, heart-felt obituary that was penned by Rev. Carl Schaub of St. John’s. Printed in Germania, a German language newspaper, the preacher stated that Maue “lived in harmony with his neighbors, as well as with all people” and referencing the makeup of our town in the period, said that “he was loved and beheld as a man of honor by not only the Germans, but by the Americans as well.” The Frankfort correspondent to the Joliet Weekly News said in a loving tone that “we did not suppose he ever had an enemy.” Franz Maue was buried at St. John’s Cemetery on March 5th, a rainy day on which the neighborhood’s single-track farm lanes were swamped with mud. Despite the gloomy weather, Rev. Schaub counted 85 carriages in attendance at the funeral.

No less a pioneer was Diederich Brumund, whose granite obelisk stands southeast of Franz Maue’s lot, being triumphantly reminiscent of the Washington Monument. Remembered by a contemporary as “honest and truthful in all things, a friend to the needy and a father to the fatherless,” he was born January 23rd, 1816 near the North Sea in a place called Sande, in the grand duchy of Oldenburg. Brumund spent his youth on the plains of northern Germany. It was later remarked that he received an “excellent education” while growing up, was noted as a “fine mathematician and scholar” and would later work as a clerk in Holland, where he picked up the Dutch language. He took Nicolina Folkers as his wife in 1843, and with four young children in tow, the family crossed the Atlantic and made their way to America in 1849. Sailing from the German port of Bremerhaven aboard the Ornholt Boming, the Brumunds navigated the choppy Atlantic for seven weeks before their arrival in New York. That August 28th, their journey ended when they picked a spot in our midst, carving out their home on the north side of modern-day LaPorte Road, a little way west of its intersection with what is now Wolf Road.

The Brumunds built a modest home and began farming, and within two years of their planting stakes, Diederich was able to buy the land where he made his home. These early days were tough ones, when everyday tasks could potentially be fraught with danger and hardship. Typical of this is the time when, on a trip carrying goods to the Chicago markets, one of the family’s oxen bolted and drowned in a canal. While he was a man of the soil, like so many of his brethren interred in this cemetery, Diederich Brumund also kept a small general store on the farm, a haven for pioneers in search of a convenience. Like more than a few of his neighbors, his farm was cut in two when the Rock Island railroad was built, and while some used this as time to seethe in anger at the railroad, this new American saw an opportunity to capitalize. On May 27th, 1853, a plat was filed with the Will County Recorder of the northern edge of his property bordering the west side of Allen Denny’s new town. Known as legally as Brumund’s Addition to Mokena, the farmer began selling off the parcels of land therein to some of the first residents of the young community.

Diederich and Nicolina Brumund's obelisk, the tallest in St. John's Cemetery. (Image courtesy of Michael Philip Lyons)

Five more children joined the Brumund fold after their arrival in our neck of the woods, and Mokena grew bit by bit, slowly becoming a small village. As the St. John’s flock came together in 1862, Diederich Brumund proved the giving spirit in his heart by being instrumental in the building of their church. He was a man who gave freely of his money when it was for the greater good, and one who also was very shrewd when it came to investing it. Aside from his large Mokena farm, Brumund came over time to own seven hundred acres in Green Garden Township, over a thousand acres in Missouri, and some land in Iowa to boot. Due to the effects of asthma, Diederich Brumund was called to eternity in Mokena on February 17th, 1885. A pillar of his church and community, he was laid to rest in St. John’s Cemetery, not far from the humble house he called home for 35 years.

These few personalities, these historic figures who grace the pages of our community’s narrative, are but a tiny sliver of all those represented at St. John’s Cemetery. A stroll through these grounds counts as an unforgettable journey into our collective past. May all who found their final resting place here be loved and honored now, just as they were in their own time.

No comments:

Post a Comment