(be sure to read Part 1 of this story, posted last week!)

When the Joliet Weekly News and the Joliet Herald became one in 1915, Mokena residents noticed immediately that the subscription for the new paper was a heftier price than that of the old News, and by and by, takers of the publication started to drop off the rolls. Local folk, who recognized Bill Semmler’s natural talent for scouting out newsy morsels, encouraged him to start his own sheet, and thus, in an extraordinary moment, sprouted in Bill’s mind the first seed of the idea to start his own newspaper that would serve the Mokena area.

In neighboring Tinley Park, businessmen who had enjoyed his coverage of their neck of the woods during his time with the News floated the idea of starting a stock company to help Semmler get a paper started. No small amount of money was raised in this endeavor, and Bill even looked over real estate there to house an office, but America’s entry into World War I threw a wrench into these plans, and they came to naught. At this point, he re-shifted his attention to Mokena, his hometown.

While the Mokena of this era was a small, rural place mustering up around 500 residents, it also boasted a rich journalistic history. The village’s first newsperson was a plucky 18-year-old named Julia Atkins, whose handwritten broadsheet, the Mokena Star, appeared in 1852, as the community was barely more than a handful of buildings along the newly built Rock Island line. The Mokena Advertiser was another early publication, helmed by Charles Jones, another young editor, from 1874 to 1877. At the same time, town correspondents using romantic monikers such as Bluebeard, Cupid, and Euripides sent in news to the Joliet papers, while in the 1880s, the Mokena Commercial Advertiser was printed in Lockport.

The Joliet Weekly News, and later its amalgamated form, the Joliet Herald-News could be counted on for Mokena reportage, especially under Ida Kiniry’s and later Bill Semmler’s tenure as contributors, but local columns were painfully short during the World War I years, often being edged out by news from the county seat. In this era, residents of eastern Will County found themselves without representation in the press. When the war ended in 1918, the question of a new, Semmler-led local paper started up anew in Mokena. A few town business people, such as auto dealer Elmer Cooper, harness maker Albert Hellmuth, insurance man Ona McGovney, as well as the Frankfort Grain Company and J.C. Funk of Tinley Park put their money where their mouths were, and promised their support in the form of advertisements.

The idea to forge ahead with a new publication was set into motion. As Bill and Margaret Semmler brainstormed what to call the paper, Mokena’s businesses were lined up on Front Street, with the Semmler print shop being a near neighbor to all. Among them were two blacksmiths, a feed shop, a livery stable, and three general stores. A grain elevator stood near the busy Rock Island depot, and Bowman Dairy maintained a milk bottling plant on Marti Street, the community’s main north-south thoroughfare. A two-story schoolhouse stood on the east side of town, while four churches provided for the spiritual and social life of the village.

Things started off modestly in the new concern; or as the Semmlers would later more candidly put it, on a “shoe string.” As their first issue was about to see the light of day in August 1919, its letters were set by hand at the Front Street office, after which the type forms were gently wrapped in paper, and then bundled into a suitcase. Bill and Clinton Kraus, a 15-year-old neighbor, hauled the luggage onto a Rock Island accommodation bound for Blue Island, some 13 miles distant. Once there, the two Mokenians took their cargo up a steep hill to an old press on Western Avenue, ownership of which Bill had recently come into. To their fortune, the press would eventually make its way to the printing office in Mokena, alleviating the drudgery of having to make repeated trips to Blue Island. Once all the newspapers had come off the rollers, they were brought back to Mokena via a return train, and addressed at the Semmler house.

The Mokena office of the News-Bulletin, seen circa 1925. The historic building stood at the site of contemporary 10842 Front Street. (Image courtesy of Richard Quinn)

On August 21st, 1919, the first issue of the newspaper was born to the world, bearing the heady title of the News-Bulletin. In a reflection of the epoch in which it was born, the News-Bulletin triumphantly heralded the return of Mokena boy Alfred Hatch from Germany, where he had been stationed with the Army of Occupation. In other happenings of the post-World War I era, the new paper eagerly reported that the village’s Camp Fire Girls had raised enough money to support a French orphan.

A week later, when the second issue landed in the hands of its subscribers, its front page held the flavorful story of Fred Steinhagen Sr., an irate Mokena farmer who had been arrested for firing a revolver at local baseball players, whose fetching of errant balls on his property he interpreted as trespassing. News from the neighboring communities of Frankfort, Marley, Matteson, New Lenox and Tinley Park was also included, along with farming and household tips, as well as some jokes thrown in for good measure.

Composed of eight pages, (with five columns to a page) it could all be had for $1.75 a year. Those first editions of The News-Bulletin had about 200 subscribers, however, by the end of 1919, the Semmlers had upped their numbers, counting a whopping 900 people in Mokena and the surrounding territory. The dramatic uptick was due to a subscription drive brainstormed up by Bill and Margaret, the grand prize in which was a $900 1920 Overland touring car, the same ultimately being won by Mamie Kolber of Mokena. In a model that was kept up for a goodly portion of the publication’s existence, news was gathered by calling local families and outright asking for it, it was also asked for in the pages of the paper itself, reminding readers early on to “Send in your news items. We went them all. Perhaps you entertained company, know of a party, of a visitor from a distance, an accident, a social affair. All these things make good news items. Just bring or send them in. By doing so, you will help to make this paper a real spicy sheet.”

By August 1921, the price of a yearly News-Bulletin subscription has gone down slightly, and would cost a reader $1.25. Touting the new price, and knowing full well that issues were being passed around Mokena from person to person, the Semmlers wrote that “…a paper is like a woman. Every man should have his own and not run after his neighbor’s.” The early period of the News-Bulletin’s existence was a tough one for the them, full of trial and tribulation. In their own words, it was a time when “the waves were high and the sea rough.” Their enterprise faced open animosity from select Mokena business people, and for reasons known only to them and lost to time, a handful steadfastly refused to advertise in the publication’s pages, who with a surly mien made it known that Mokena did not need its own paper, and openly urged Bill to quit.

The Semmlers also had to take on no small amount of debt to get the News-Bulletin off its feet; this being something that they were still wrangling with five years after the first issue came off the press, when Bill wrote that “everyone he is indebted to will be paid in full with interest to boot.” At this point in the paper’s young life, it missed its only issue. Due to a strike involving the Western Newspaper Union in Chicago, a supply of newsprint failed to make it to Mokena on time. The arbitration dragged on for a few weeks, but after having had his fill after the first week, Bill went to the city himself and scrounged up a supply of paper, which he carried back to the village wedged under his seat on a Rock Island train. After this episode, and having learned their lesson, the News-Bulletin office began to regularly carry large supplies of it.

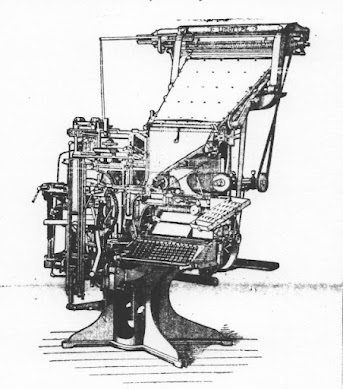

Bill and Margaret Semmler were the brains behind the News-Bulletin, but they had plenty of help from technology. An invaluable machine called the Line-o-Graph made its debut in Mokena on the last day of 1919, and while it wasn’t actually up and running at the office until January 6th, it revolutionized the Semmlers’ ability to print the news in town. Where the work of composing the paper’s type was once done by hand, the Line-o-Graph now did it mechanically. In showing off the contraption in the pages of the News-Bulletin, the Semmlers noted “We do not believe in boasting, but the fact is that this machine is a boost for the News-Bulletin, as it gives us fine equipment, such as is seldom found in a small town.”

For all the good it did, the early days of Line-o-Graph ownership were a source of a seemingly never-ending stream of vexation. One headache that cropped up were complications with the machine that resulted in the January 16th, 1920 edition coming out late. In an apologetic blurb, Bill wrote that he “felt much aggrieved that the delay had taken place” but then proudly stated that “we have now tamed the wild animal.” The new publication got another boost up when a two magazine Mergenthaler Linotype machine was installed in June 1923, it being a more prominent relative to the Line-o-Graph.

A 1923 view of the Linotype, a vital piece of equipment in the Semmlers' shop.

This depiction of the family's press appeared in a 1925 edition of the News-Bulletin.

A major technical annoyance for the Semmlers was their old Diamond cylinder press, a contraption they loved to hate. In 1925, Bill wrote that it was behaving “like a balky mule” and that it could only be operated “by a wizard and hypnotist”, before adding that he “had lost much patience and religion in wrestling with this demon of a press.”

Another advance occurred in March 1925, when a new cylinder press, a Century Two revolution model, was set up at the Front Street office. This marvel was able to produce about 2,700 impressions in an hour, which saved the Semmlers and their employees much time, cutting their final production time in half. Prior to the installation of this machine, it would take almost five hours to print a run of the News-Bulletin, but with the new press, it came down to an hour and a half.

For a period early on, the Semmlers employed an assistant editor, having hired E.E. Turrentine in May of the paper’s first year. Things were still wobbly as the publication tried to find its footing in Mokena and the surrounding area, with more delays in publishing and a piece on the front page of the May 14th, 1920 issue that lamented the News-Bulletin “has had a thorny path to travel on account of a shortage of help” and also vaguely noted “some dissatisfaction among the subscribers.” In an instant, it looked as if everything might literally go up in smoke, when on August 6th, 1920, a freak gasoline explosion erupted in the paper’s Mokena office. For a few panic-filled moments, the situation looked utterly hopeless, but through the quick-thinking bravery of some neighbors and Bill’s mother Catherine, who lived in the rooms adjoining the office, the flames were tamped down. In a piece on the fire that appeared on the front page of the following week’s paper, Bill soberly described himself as having been “enveloped in flames” and having to beat the fire out of his clothes. Assistant editor Turrentine was unlucky enough to have his foot burned and back wrenched when the explosion, in a close call, wedged him between the Linotype and the cylinder press. All of that week’s news from Frankfort and New Lenox was lost in the blaze. In talking about the incident in the News-Bulletin, the Semmlers humbly thanked everyone who helped rescue them and their property.

Being headquartered in a historic building had its share of problems, too. One was flooding, which occurred in the old cellar under the structure. On one occasion in March 1922, a clog in a drain caused fourteen inches of rain water to stand in the basement, requiring Chief Herman Schweser of the Mokena Fire Department to blast out the obstruction with the village fire hose.

By the mid-1920s, the News-Bulletin bore the slogan “Cussed by Some – Discussed by Many – Read by All.” While the publication had a comfortable number of subscribers, all was not a rose pedal path for the Semmlers, as their straightforward sense of local journalism sometimes incurred the wrath of certain readers. A classic example would be the blistering fallout that reared up in the aftermath of a Prohibition era raid. In October 1930, a tip had reached the Will County state’s attorney that illicit booze could be had at a Mokena ice cream parlor, and when special investigators came to town, they discovered almost five jugs of moonshine and two barrels of beer on the premises. Edward Martie, a village trustee, future mayor and father of one of the shop’s owners, “grew violently angry” that his son’s name was published in connection with the police action, and “threatened dire vengeance” on Bill Semmler. In detailing efforts that had been made to cover up the news, Bill wondered on the News-Bulletin’s front page if Martie “favored the suppression of all news bearing on liquor raids, or does this suppression only apply to favored individuals?” while also stating that “Those who engage in illegal business must expect to stand the consequences.”

Another occurrence was particularly ugly. In the spring of 1931, when local tempers boiled over an issue regarding the installation of a central sewer, an unknown party attacked the News-Bulletin’s office under the cover of darkness and painted the windows yellow. In a front page piece on the incident, the Semmlers asserted that “dirty politics are being resorted to” and also that they knew who was behind the lark. Referring to the guilty party, it was written that “the opposition hates publicity, and because this paper dares to print the facts, they go around saying that only lies are being printed…” It was declared that the paint would stay on the windows until after the coming village election.

As the News-Bulletin’s readership grew, it could be solidly depended on for stories not just from its Mokena home, but also for the neighboring villages of Frankfort, Marley, New Lenox, Orland Park and Tinley Park, and sometimes even carried items from Green Garden, Homer, Matteson, and as far afield as Oak Lawn. Interestingly, by the end of the summer 1921, the paper counted at least one overseas reader in Germany. William Hoffman, a farmhand who had worked for Mokena brothers Charles and Julius Hirsch, had returned to the land of his birth and was receiving the publication there. In a happy letter back to friends in the village filled with no small amount of pride for his adopted community, Hoffman wrote that he “is very glad to get his home paper, greatly enjoys reading it and in showing it to his friends.”

This ability to drum up news from nearby communities was a keystone to the Semmlers’ success. In conjunction with the News-Bulletin, the family went on to found several other newspapers in Eastern Will County and Southern Cook County. One, the Tinley Park Times, was born in 1925, when business people and residents of Tinley Park began “clamoring for a paper of their own.” The community had long standing ties with Bill Semmler, having asked him to work there as early as the World War I era. The Times was so successful that the family opened a printing plant in the town in the spring of 1941. Another jewel in the crown of Semmler Press was the Orland Park Herald, which debuted in 1926. In terms of layout and content, these publications were very similar to the News-Bulletin, with the articles on the front page being swapped for eye-grabbing happenings of each respective community.

As the years carried on, the News-Bulletin became a Mokena mainstay, and as the country entered the Great Depression, the Semmler family and their publication were able to keep their heads above water. Reflecting the dark economic situation in the country, the columns of the paper charmingly noted in October 1931 that they were able “to help relieve the depression to a small degree” by remodeling and expanding the printing plant attached to their Front Street office to its new dimensions of twenty by forty feet. The News-Bulletin got a leg up on the afternoon of January 18th, 1933 when it, along with the Orland Park Herald and the Tinley Park Times, were boosted over the airwaves of radio station WCFL of Chicago. Bill himself gave a “community talk” on each of the communities served by these publications, which was in turn accompanied by a musical presentation.

The News-Bulletin office in Mokena was a veritable hive of activity. In addition to the newspapers that rolled off their machines under the umbrella of the Semmler Press, the family also continued to take on general printing work. In August 1940, after being in business for exactly 21 years, a column noted that “today the shop of the News-Bulletin is a busy place. Three weeklies, one bi-monthly, and two monthly papers are printed here” while also proudly stating that they could take on color work as well as the traditional black and white. At that time, the nearly 100-year-old building was home to a cylinder press, two jobbers, a casting box, stitcher, large paper cutter, electric saw, an addressing machine, and “loads of metal and wood type.”

One of the most influential figures in the history of Mokena, Bill Semmler is pictured here at work in 1941. May his memory live eternal.

While Bill Semmler’s name appeared in almost every issue as editor, the contributions of his family members to the News-Bulletin can’t be overlooked, for Mokena at large was lucky to have in its court three women who gave their all to the paper. Margaret Semmler was essentially the paper’s co-editor and her husband’s equal in the publication’s composition and management, for many years maintaining the social pages. Referencing the famous editor of The Washington Post, another reporter would years later sublimely call her “the Katherine Graham of Mokena in her day.”

Starting in her teen years, Bill and Margaret’s daughter Adeline learned to operate the vital Linotype machine, while her sister, Ada Semmler, who felt timid around the printing plant’s loud, clanking presses, handled things in the office. On Thursday nights, getting the week’s paper ready for its Friday publishing date was a family activity. Reflecting on the late nights spent with tricky machinery, Ada would later say that “If all went well, we would go home around midnight! If not, it could take until 2:30 a.m. to finish.” Her mother Margaret also wryly wondered why they needed a house when the whole family spent so many nights toiling in the office.

Adeline Semmler in 1938.

A 1938 likeness of Ada Semmler.